Sedge og caddis? I’ve been told that caddis is the common term in America, sedge the common term in the UK. I don’t really know and it doesn’t matter much, since I think most people know that both terms cover the same insect. Caddis is a very important food source for trout and grayling. They are abundant in both still- and running water and generally not as clean-water-dependant as many mayflies and stoneflies are. Some species grow quite large, so they also represent more protein pr. bite than smaller insects.

Trout and grayling eat them in all their lifecycles. As pupae, emergers and adults. There are generally three different categories of caddis: The case builders, the net spinners and the free roamers, but since we’re dealing with the emerging/hathing pupa today, that’s a topic for a different blog.

I’m not sure if it’s true for all species, of which there are many. In Denmark alone over 170 species are recorded. But at least some of them have a special behaviour that makes them very, very visible to trout and grayling as they emerge. The pupa rises to the surface before they begin making their way to shore to complete the transformation to the winged insect. The swim actively, some quite fast and yet, trout and grayling seem aware that in this stage, they are easy prey, nearly unable to escape.

On a calm evening (they often hatch during the evening, even the night) on a calm surface, they are active enough that they are easy to see. Movement is probably more important than imitation, when hatching caddis are on the menu and in his classic book, “Flugbinding på mitt sätt” (Fly tying my way) by Lennart Bergqvist, he presents “Superpuppan” – the Super Pupa. The Super Pupa is exactly the type of fly designed to imitate movement and behaviour more than a specific insect.

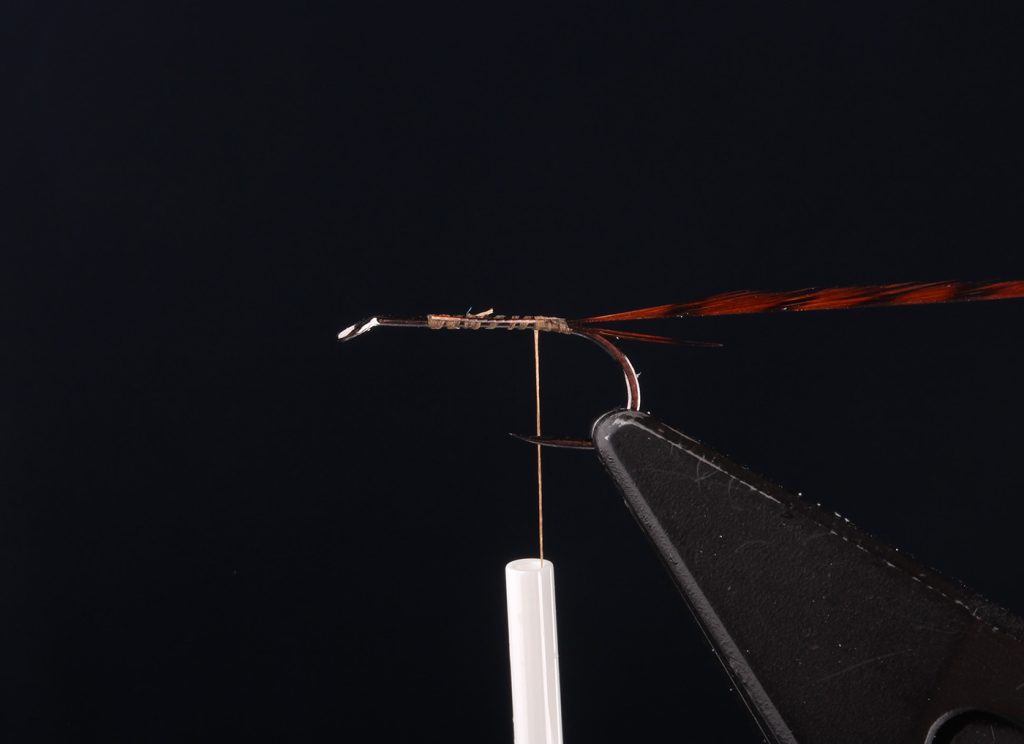

A simple, two-toned dubbed body and a palmer hackle, clipped both on the under- and overside and that’s it. You can even use a fairly long fibered hackle as some species have quite long legs. And you don’t need the best quality hackles either. Follow along with Håkan Karsnäser below and see just how simple this effective imitation is to tie.

Lennart Bergqvist points out in his book, that the fly can be fished in almost any way imaginable. Static, actively, dry, damp or even sunk.

A good selection of Super Pupae in sizes from 10 to 18, even smaller, is always good to have. They are excellent when caddis are hatching, of course, but especially the smaller ones are also good get-out-of-jail-flies. For when the fish are feeding in or on the surface and you can’t see what they’re rising to. And September is a great month for caddis.