Svend Saabye in the process of signing his iconic book “Lystfiskerliv”. Photo: Søren Glerup.

Svend Saabye

Svend Saabye was an artist and fly fisher from Denmark (1903-2004). He was an important figure in the Danish artist community and motifs from nature is what dominated his artist’s career. Nature was a constant factor in Saabye’s life, because he was also among the first to write in Danish and more extensively on fly fishing. He was quite a prolific writer and his most important work is, “Lystfiskerliv”. For a proper translation this title needs a little explaining. “Lystfisker” is Danish for a sports fisherman, but without the “sport” – it translates more directly in to “a passionate fisherman”. This book was more than anything about his love for nature and fishing. Another important publication is “Fluefiskeri efter ørred og stalling”, “Flyfishing for trout and grayling”.

Svend Saabye was an important figure in the development of fly fishing here in Denmark and apart from his love for the Danish streams and lakes he travelled to Norway for salmon.

Søren Glerup knew Svend Saabye, as well as many of the others nestors of fly fishing in Denmark, and has allowed us access to manuscripts previously published in a Danish hunting and fishing journal “Jæger og fisker”, which we’ll be bringing here over the coming months. Saabye’s artist background of course meant that he painted and drew fish. We hope you’ll enjoy these musings and drawings by Saabye.

Flies in the Head

From: Jæger og Fisker, November 1953

No one owns the light that reflects in the stream’s water under the evening sky’s clouds. No one can catch the swallow in flight as it traces its invisible path along the reed edge, over the willow tree, tirelessly playing with its own reflection. But the swallow catches in flight, each dive towards the water surface, each rise has its goal.

The stream pushes its water between water lilies and milfoil, which follow the current in rhythmic twists, a reed nods in time, another quivers like a string and reveals life beneath the shiny surface.

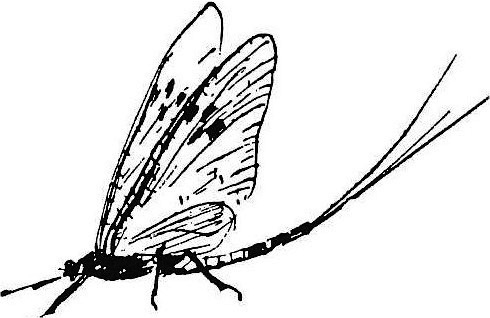

A dot appears, rises gently whirring and dark against the clear water, then light against the hill and forest in the west, then quickly rising dark again against the sky, where it disappears into the swallow’s mouth. Thus quickly ended the mayfly’s life, without reaching its wedding dress, it was granted 20 seconds of its already short fate. One by one they rise, as if born of the silent water, whose coldness hinders their first wing beats. With untested consciousness, they fly into the jaws of annihilation, unless a dorsal fin cuts the water surface and a tail fin’s slap makes them the trout’s prey. Who comes first? Sometimes the swallow in a dive brushes the water and picks up the insect.

The fisherman enjoys the privilege of sharing the goal with the bird and the fish. For the lover of the dry fly, all sport begins with the fly, both the living and the artificial. For the methodical fly tier, tying the fly begins at the stream, with an insect net he takes part in the trout’s and swallow’s catch, thinking in their elements, water and air. With the catch in a jar, he has the means for accurate observation. The mayfly rarely appears singly, in hundreds they leave their nymph life under the water at certain times of the day. There are many species, which vary with the seasons and the character of the streams. Even in the same stream, the species vary according to the bottom conditions, the strength of the current, and the vegetation.

The evening and early morning by the stream are filled with movement. Low over the water, the caddisfly circles. The crane fly tumbles in when it clumsily seeks rest on reeds and sedge. But there is something particularly captivating about the mayfly, not only because of the beauty of its poetic twilight life, but also the fish and the swallow seem to prefer it. The fisherman is enchanted by its flight and distinguishes the species from each other as the hunter does the birds. Newly hatched, they fly in a heavy and direct course towards a shelter, trees, or reeds far inland, to shed their cloak there. Like a miracle, they crawl out of their skin, with wings, legs, and tail threads. Transparent with colored eyes and iridescent wings, they take off for the mating dance, a floating play with the evening wind. Golden in the low side light of the sun, they hold their wedding in the air. The male grabs the female and rises towards the sky, only to release her after a dive almost to the water surface. Then you see her seeking upstream for the place where bottom conditions or vegetation are right. In pauses, she lands and lays her eggs in small portions, finally with outstretched wings being caught by the current – and perhaps by the fish.

In the midst of this peaceful evening hour of nature, the fly-catching fisherman hops, runs, and jumps around. Fencing in the air with the net and sweaty on the forehead, he sends furious glances at the audience. But with filled jars, he can return home to a magnifying glass, microscope, and an insect key. He can feel his catch, pin it in an insect box, or put it in small jars with formalin solution, to preserve it for comparison. Newly hatched insects molt in captivity. The males are easiest to determine, but by using the insect net quickly, both male and female can be caught together in the dive during the mating game.

If the insect is to be of real use during the tying of the fly, it must be used alive. Dead, it loses its sharp gloss, dries brownish without the transparency that makes it so difficult to imitate. Accurate studies are necessary, one viewpoint is not enough. Both the real and the artificial fly must be seen in backlight and front light, in clear daylight and sunshine. They must be seen together resting on water from the fish’s viewpoint through the bottom of a clear glass.

Books on fly tying and fly patterns can show the fly tier what is used for making flies, also what a particular insect has been imitated by, but they cannot replace the study of nature. The heterogeneity of the tying materials is one reason, another is that insects of the same species can vary significantly from one stream to another. Studies of the history of fly tying show similar variations in tying style for the same fly.

Even good experiences with a well-renowned fly pattern do not guarantee the fisherman that he has the best means at hand against the trout. Only through accurate observations and experiments does he gather the experiences that develop the sport from dubious theories to a clear method. This also applies to wet fly fishing.

Fly fishing begins with knowledge of insects under the water, on the water, and in the air.

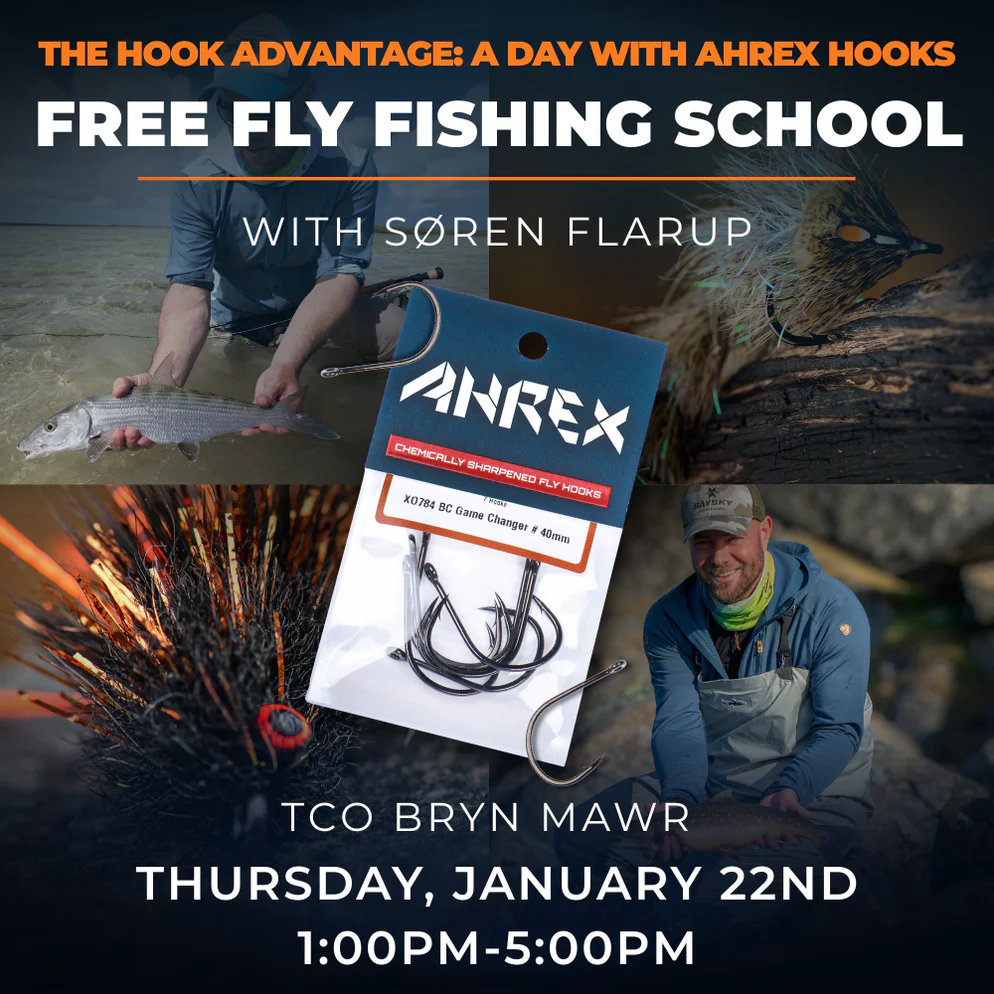

The Hook Advantage – A Day with Ahrex Hooks at TCO Bryn Mawr

Thursday, january 22. If you are in the area around Pennsylvania and TCO Bryn Mawr, we hope you will come out and meet Søren Flarup, the hookmaster at Ahrex and Steve Silverio. Søren will be talking hooks, giving out samples and previewing the new offerings in the Ahrex lineup, including the new Gamechanger, designed in collaboration with Blane Chocklett.

You can read more here:

And Next weekend – january 23, 24 & 25th we will be at The Fly Fishing Show in Edison, NJ. It’s held at the New Jersey Convention & Expo Center.

Read more about the show here: